I looked up high at the giant T-Tail over me as I stepped off the big white bus and waited there on the tarmac by the Red Cross.

Waiting for the medics to move their convalescent patients out the back door and up the ramp, the reality of transitioning my fighter-pilot mind from prepping to fly a sunrise Dawn Patrol mission over Afghanistan, to loading up, instead, on a Medevac C-17 bound for Germany at 10 in the morning hit me like an anvil. I turned around quickly to see jets ripping through the cold air, a two-ship of our very own Chief StrikeEagles - getting airborne over the runway next to us and driving the point firmly home for me.

It was January 21st 2008, I was leaving the war, and I was in shock.

6 hours earlier just after 0400, I was in the Cadillac shower near our plywood B-Huts, showering for the day and thinking of rounding up our 2-ship to drive my white Chevy Silverado pickup to the other side of Bagram for our sunrise mission. But something was off....my left ear felt like it was blocked, like it was full of water. I stood there in the skinny Cadillac shower, using up all the hot water in the dark- pulling on my earlobe and working a valsalva to clear it while cursing the head cold I'd been dealing with that everyone always gets just after deploying to the Middle East. A mild illness sweeps through the squadron just after every unit arrives in country, and we all just sort of deal with it; I thought I was over it. Today, however, I clearly wasn't over it, and my left ear wasn't clearing despite my best efforts. You can't fly with a blocked ear....I changed quickly, found the guys and gave them the keys to my white Chevy Silverado.

"I'll be over at the squadron soonest after seeing the Flight Doc; standard brief- and we'll talk the details once you check in at the squadron with Top 3; I'll call over."

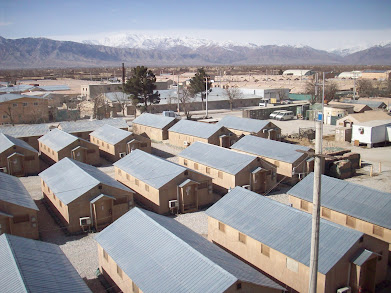

B-Huts where we lived at Bagram

"Boss, I want you over to the hospital right now, I'm calling to get you into the booth. You're not hearing right, and we need to know what we're dealing with."

B-Huts where we lived when not at the squadron

B-Huts where we lived when not at the squadron

Landstuhl Hospital Outpatient Barracks

It was an interminable wait to fly. And every day, I went to the hearing booth to practice hearing...better... praying every single day for it to get just good enough for me to fly again. I tried every posture, every pose, every position imaginable in that tiny booth, taking out the chair and laying down with my feet up the walls- holding my breath - exhaling inhaling exhaling - squint - mouth open - hold - BOOP BOOOP BOOOOP. "I HEARD IT!!!" But only at the loudest volume... I needed much more. And each day, I got more.

.JPG)

.jpg)

335th Chief Jets in the Revets at Bagram

Bagram Plywood B-Huts.

-----

"Sergeant. ....SERGEANT! You're testing the WRONG EAR." I had opened the door to that little cube hearing booth in the back corner of the Bagram hospital, really testy that this whole process was going to make me late for our 2-ship brief and the Close Air Support mission we were scheduled for. I was uncharacteristically short with this medic, because I had just spent what felt like 15 minutes in that little box with zero sounds in my left ear, but plenty of noise in the right. BOOOP BOOOP BOOOOOOP. I assumed he had his settings wrong, and now I needed to drive quickly over to the squadron to launch on time.

Strike Eagle in the revets at Bagram

"Sir, to be honest with you," said TSgt Smith, "We've been running audio tests on your left ear the WHOLE TIME. What you are hearing in your right ear is the sound being conducted through your skull."

Looking at him in shock, I pulled myself slowly back into the tiny hearing booth- stunned, embarrassed, angry, and confused as I shut the door and considered my new reality.

Aeromedical Evacuation C-17 scene. Wounded patients secured on fixtures.

A few hours later at 1030, I was in the business end of a giant cargo plane, contemplating the bizarre juxtaposition of me in a flight suit, walking tall up the ramp and completely fine - contrasted with the scene of our wounded troopers being carried on stretchers from the back end of the bus. Aeromedical Airmen in tan flight suits like mine were buzzing all around to take care of each one with utmost care, moving them up to install them onto their fixtures in the cargo section of the plane -

"What the heck am I doing HERE?!" I demanded inside my head, the noise of Bagram flight-line operations and running jet engines filling just my right ear as I sat down by the wall in a red webbed-canvas seat.

They cranked the jet, we left Bagram, and over the Caspian Sea on the long ride to Ramstein, Germany, I gained a newfound respect and appreciation for our Aeromedical Evacuation crews and for the soldiers they were taking care of in the back of that C-17. I didn't feel like I deserved to even be on the plane with these heroes, but here I was, and it was just an incredible scene playing out in front of me.

So professional, so caring, so attentive, and so good. I began to realize I was entering a strange world I had never known, a completely different universe of medical care, and these pros knew exactly what they were doing.

We were in good hands.

Bagram B-Huts where we slept

Two hours before, slinking back to Doc Flower's desk after my moment of humility with the Sergeant in the hearing booth, we had a very difficult chat together. Doc Flower, always smiling, always positive - looked at me this time with a deadly serious face as he stretched out his arm and said to me: "Boss - here, I want you to eat this - and I want you to eat all of it, right now." I looked down at his hand, opened my palm as he dropped a fistfull of pills into my hand. It was truly a giant pile of pills.

"It's prednisone steroids, and the blue ones are antivirals. Lemme see you Muck It Down," he said, handing me a bottle of water. I mucked it all down. "Ok, I have you on the next C-17 to Landstuhl. What you have is a case of 'sudden senso-neural hearing loss,' and we need to get you there soonest. I've called the squadron, your two-ship is ready to go for the mission and and is covered. All you need to do is get packed and be at the hospital by 9 to get on the big white bus." The rest of our conversation wasn't pleasant, and I was pretty hard-headed about it - but he got through to me the way Doc Flower always does.

I didn't like his plan.

B-Huts where we lived when not at the squadron

B-Huts where we lived when not at the squadronBut - I packed a bag quickly in my hooch, hitched a ride to the squadron to see my #2 - our Ops Officer, "Saint" Bernard, and I gave Saint the squadron. There's nobody in the world better to trust with that kind of a thing than Saint Bernard, but here I was, a Combat Fighter Squadron Commander, IN COMBAT, IN AFGHANISTAN, just getting started with our deployment and a handful of missions under my belt and Now I'm LEAVING???!!"

Even now, my feelings from that morning are hard to write about, but at that moment, my hearing seemed like a minor annoyance, while the squadron and our F-15E Close Air Support combat mission was everything to me. It was a tough conversation for me. But Saint was... a Saint. Of course it would be fine.

And I was off.

Ramstein offloading for the Landstuhl hospital

We landed in Germany, and I walked down the ramp with the others on the plane who weren't bound to a stretcher. "Lieutenant Colonel Jinnette!?" yelled a man in camo at the base of the ramp. "Hey sir, I'm Tech Sergeant Johnson. I'm here to get you where you need to go!" I could see other Airmen all around the end of the plane like Tech Sergeant Johnson doing the same for those coming off the C-17 - and each patient had a handler, a personally-assigned escort to shepherd them into the Landstuhl hospital. It was late in the day, and I had the sense only the most critical of these folks were going to see medical care immediately on arrival.

Sergeant Johnson had been temporarily assigned to Landstuhl from his stateside post - and was just there for a 3-month stint. After checking me in at the registration desk, he scheduled me with the ear doc for an early morning appointment, and then began taking me to a whole set of unexpected stops to get me situated in the new system. Using a silver BMW 5-series sedan, he explained that he shuttled his patients to various appointments using the car outside the hospital and was responsible for the care of a small set of wounded folks making their way through the Landstuhl healing process. He oversaw all their appointments and made sure everyone got where they needed to be on time.

I really wasn't expecting to be going to the base BX (department store) in a BMW after landing, but that's where we were headed. Pulling into a spot in the lot, Sergeant Johnson handed me a piece of paper and said "Sir, you really don't know how long you'll be here. This is a $150 voucher for some civilian clothes in case you need them long-term. Go in, pick out a pair of jeans and a couple of shirts and show them this and you'll be all set - I'll wait here for you. (I still have those clothes by the way.) Next stop is the hospital sundry shop so you won't need any toiletries here; they open in 20."

After returning from the BX with a bag of new clothes, marveling at all the German items in there I'd never seen before (cookoo clocks, etc), our next stop was a small glass room just inside the entrance to the Landstuhl hospital. Seeing a dense crowd of clearly wounded soldiers in the room, I hesitated, thinking best to give them all their space. "Go on sir, that stuff's for you too! Get whatever you need and plan to be here for a month."

...After wincing from the sound of those words, I walked in, and immediately noticed a giant, bald General Officer in the room who was shaking hands and chatting with all his soldiers. I recognized General Odierno, and knew he was deployed in Iraq for the surge. Apparently he was on a trip here at Ramstein and was seeing his wounded troopers who had been flown in to Landstuhl from Iraq.

"One of these...is not like the others!" I really stuck out like a sore thumb in my bright tan flight suit and my half-grown-in bullet-proof mustache as General O shook my hand too, and he looked at me as if to say: "What the heck are YOU doin in here, Air Force?" I felt the same way, as I picked up deodorant, boxer shorts, shampoo and t-shirts from bins stacked all around the glass room for in-processing patients.

12 hours earlier, I was prepping for a combat sortie. Now, I was picking out boxer shorts for a month-long hospital stay, surrounded by truly-wounded soldiers in wheelchairs or crutches, all with serious injuries on their bodies. I felt ridiculous.

Our next and last stop for the night was the barracks- truly Army barracks- complete with two pages of Army rules and an orange vest to wear outside for daily accountability formation at the 0600 morning muster. "ACCOUNTABILITY FORMATION?" "MUSTER!!?"

I was in Army hell.

What I experienced over the next week at Landstuhl hospital, however, was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. MRIs. Dizzy tests. All kinds of checks on my hearing and my head and my health and my balance and my whole body. So thorough and so professional and so good. Incredible doctors and staff at every turn. And all the while, Meredith back home working a speedy passport renewal to come over, with Landstuhl docs thinking and telling us I could have a brain tumor or something really bad.

Muster in the morning with my new Army buds at 0600 in my orange vest - then tests all morning till noon when I was released back to my Barracks room. I had a perpetually-pounding headache and an increasing feeling of aggravation from the high-dose steroids I was taking all day. Lots and Lots of Steroids - to reduce the inflammation inside my ear where the docs believed my cold had crept up inside my eustachian tube and attacked my cochlea. They began to believe the nerves supporting the villi hairs in my inner ear had been severely damaged by the infection and inflammation, and were hoping that the steroids would stop it in time to save me from permanent deafness. Would the nerves grow back?

Landstuhl Hospital near Ramstein Air Base, Kaiserslautern Germany

Since all my tests and appointments were in the mornings, in the afternoons I was completely free. And although I was expected by protocol to stay in my barracks and deal with the prednisone headaches there, the train station three blocks away called my name every afternoon for points east and west across Germany. I figured if I got back home by 0600 with my Orange Vest to stand tall with my new Army friends, I was properly and usefully living vicariously for my brothers back at Bagram who did NOT have the opportunity to chase prednisone pills down with a German Pint in Heidelberg, paired with delicious Schnitzel.... Sorry not sorry. Trier too... Manheim...Saarbrucken... They all had excellent prednisone-pairing-pints.

Kaiserslautern Train Station

What I learned on those afternoon train trips was that you really do need two good ears. Without a left ear, you realize that you actually listen to your feet when you walk - and it helps you walk. Without that ear, you have to think about walking differently. In a parking lot, two good ears help you know where the car that just cranked is. Crossing a street, you need both to know from which direction the old-school Mercedes SL is coming from. Directional sound is gone. At a train station, you need both to navigate the crowds. I learned that without two good ears, you really are more handicapped than I ever realized you could be. And it was not good.

And I was in low spirits because the docs were giving me zero hope I'd ever hear again on the left side, and with that realization came the thought that I'd never get back to my squadron at Bagram, never get back to lead combat missions with my Chiefs again, and that, most likely, I'd had my very last F-15E sortie, ever, in a Strike Eagle. I was more concerned about all that than I cared anything about my hearing. It was a low time for me in those Army Barracks with time to myself. What also surprised me that week was how emotional the prednisone was making me. Every feeling, high or low, good or bad, positive or negative - seemed ridiculously amplified to an astonishing degree. I felt ecstatic with good news and I felt something like 'roid rage' with bad news from the docs. I quickly began to realize that I needed to monitor myself very carefully with all the pills in my system.

..Maybe that's why they wanted me to stay in the barracks...

But the most profound experience for me, the Air Force guy walking around Landstuhl in a tan flight suit - was the volume of severely-wounded American Fighting Soldiers receiving care all over that facility. Limbs missing. Soldiers in beds with legs up in traction. Wheelchairs. Crutches. Prosthetics. Large wounds and bandages. Severe, real, combat, wounds from road-bombs and firefights in Iraq and Afghanistan, places where I had dropped bombs in anger taking care of men like these from above during firefights. It changed me. And every trooper I saw had a determined look and a fighting attitude that made me both proud of them and proud of America, and at the same time almost embarrassed to be in the same place with them with my relatively minor infected ear thing going on. My situation didn't even come close to what these guys were experiencing, and they astonished me and inspired me with their spirit. To this day, I remember their faces, their determination, their shock, their gravity, and their presence in those Landstuhl hallways.

One of the most memorable moments during my time in that hospital was late in the evening when I was in checking on some of my medical test results in the system. A lady, probably an Army Spouse, walked in with the most beautiful Bernese Mountain Dog I've ever seen. Wearing a bright red shirt and jeans, she exuded happiness and friendship, and explained to me that she and this beautiful vest-wearing pup visited all the serious patients every night to help cheer them up. I wasn't in that group, but I have to say, she and her pup really cheered me up, too. I really needed exactly what she gave me that day.

Six days after arriving at Landstuhl, I was on a plane back to Bagram! Joyfully, I had learned, after every possible test they could subject me to (cold water jets in my ears were the best!) - that there was a very slight hope that my hearing would improve, and that my prednisone was helping the inner-ear inflammation to recede. In my debrief meeting with the Landstuhl ear doc, he said, "You're really lucky your Flight Doctor gave you that Prednisone when he did. We had another soldier come in from a Forward Operating Base this week, and they delayed his treatment - it was too late for him - he has no chance of recovering his hearing." What a reality check.

He relayed my plan from the Flight Docs back in DC: "Go back to Bagram, take your prednisone, taper down the dosage while testing your hearing every day in the booth to monitor progress. If and when you meet the min standard (~50% hearing on that ear) we'll put you in a cockpit with Doc Flower, you'll do a intercom hearing test in the jet, and if you're able to understand what he says from the back seat, you'll be cleared to fly combat missions again."

Hearing that news, I was thrilled! And my happiness was augmented by the steroids...I was literally the happiest guy in all of Germany. If nothing else, I just wanted to get back to my squadron mates at Bagram and back closer to the fight. And the best case...I was a combat fighter squadron commander: I wanted to fly more than anything. I had my mission clearly laid out for me. Get my left ear to 50%.

335th Squadron Duty Desk at Bagram; Hammer Castillo running the show.

Another view of the Chiefs' Duty Desk at Steptime

The Bing. Our TV room by the B-Huts.

The next days were surreal. I was back in Command, back in the Squadron - but I couldn't fly. I was on a roller-coaster ride of 'roid-induced emotion, but I couldn't let any of that show to my squadron. Simple things made me either too happy or too sad or too angry or too glad, and I found the need to shut my office door more than a few times to separate myself from the squadron so I didn't say or do stupid things. It's hard to explain how the high-dose steroid drugs impacted me, but in short, it was a continuously-pounding headache, coupled with firewalled emotions at the edge of personal limits, and total boredom - all mixed together. And the tinnitus...

As my nerves were slowly healing- what I was hearing was an extremely loud roar, joined by an endless series of loud tones striking at different frequencies; octaves. It was like a 3 year old with a xylophone. The noise in my left ear was as loud as standing by a running jet engine (severe tinnitus), while my right ear was hearing squadron mates talking to me normally. What was going on inside my head was overwhelming as I was processing all that sound coming at me differently, and it was quite a difficult challenge.

At one point, Lieutenant General North visited our squadron and planned to give a recognition coin to two of our youngest guys, Mach and Scudz, who had done an amazing job protecting troops and civilians in a very difficult fight. I was standing in front of the guys in the squadron there with General North, doing my best to say all the right things - while inside my head, the noise and the maddening musical tones were deafening and overwhelming. It sounds like an exaggeration, but that moment and that ceremony was one of the most mentally-challenging things I have done. I went back into my office and recovered for an hour after Lt General North left the building.

Inside the squadron at Bagram.

My office- first door on the left.

Briefing rooms down the hall; vault in back

I couldn't fly, but I made the best of the situation. I studied in the vault. I looked at combat tapes to learn from everyone's hits. I read intel reports. Valentine's Day came with boxes and boxes of pink care packages from kids all over the USA. We watched the Super Bowl and half our squadron taunted every Patriots fan (the other half) as the Giants upset the Patriots 17-14. We grew our mustaches thicker and sang songs together and smoked cigars and drank near-beer in the snow at the Bing, by our entirely unsafe fire - in our entirely unauthorized fighter pilot firepit - in the middle of a sea of highly flammable plywood B-Huts.

I walked the line out by the jets with our maintainers and went out to see them in the snow at 3 am in the cold, gloves off, hammering away at a stubborn nose gear situation that was keeping them from getting the next lines ready to launch. Incredible dedication. Our youngest maintainers were out there in the dark and snow getting it done together.

335th FS Chiefs watching the Superbowl.

Giants beat the Patriots 17-14.

.JPG)

At the Bing with the CHIEFS

My hearing improved every so slightly every single day, as I learned the system and my nerves healed up inside my ear. I became a fair expert on the BoopBoopBoop cycle, to the point where I could pretty much predict when to push the button based on timing alone. After a while, the Airmen running the tests for me quit harassing me for false button-pushing, so I knew I was getting better.

This is Doc Flower.

Doc Flower saved my hearing with a fistfull of Prednisone.

I am forever grateful.

Finally - the day came! My hearing was just good enough to meet the min USAF flying requirement, and Doc Flower got approval from the doc bosses in DC for me to do the test in the jet with him. Thinking positively, we coordinated to arrange a unique crank plan and briefed up for my hearing test to be an actual combat sortie:

I'd have a backup pilot brief with us, and Doc Flower would join me up in the jet with my (WSO) Weapons Systems Officer, our UK Exchange officer "Crawfs' Crawford standing by on the ground. I'd crank the right engine, Doc Flower would read me 100 lines from an approved Air Force hearing test, I'd say them back to him, and if I passed (which I, of course, would...) Doc Flower would jump out, Crawfs would climb up the ladder with the right engine running - I'd crank the left engine and we'd lead our two-ship mission into the air. If for some reason I failed (which of course, I wouldn't...) I'd shut down, and my spare pilot would swap with me to lead the mission.

With Crawfs Crawford, 20 Feb 2008, after the flight.

"Good to go, Boss - You're all set! 100%! I'm out."

On February 20th, 2008, I passed the cockpit test with Doc Flower. Phrases like "the corny aero split the bleak tank" times 100. Never have I enjoyed a hearing test more that that one. Doc Flower cleared me to fly, unplugged, hopped out of the seat, and Crawfs jumped up the ladder.

High Tactical Initial over Bagram, Afghanistan

Hearing his comm cord plug in, "All set, Crawfs?"

..."Nowhere I'd rather be, sir - Let's DO THIS!"

I spooled up #1 of our Chief flagship, tail #487, feeling the giant intake ramp SLAM down behind my left shoulder, once again sensing this magnificent machine fully awake and alive all around me as I closed the canopy. It had been a very long wait to get back in this jet. With a thumbs up from Stryker Haley and Flak Willis, and we taxied out of the revets to runway 5 and launched on what would be (and still is) the greatest flight of my life.

335th FS Chiefs Bagram Departure

5 hours of pure happiness for me, and to be honest, I was sort of grateful that we didn't have any Troops-In-Contact situations to deal with on that day. Getting back in the saddle after a month off was a bit of an adjustment - with my new ear situation and all the tones in my head still ringing - but they were much reduced from the previous month, and I was so grateful to God to be back in the air again.

.jpg)

With Crawfs, 20 February 2008!

Greatest Flight of my Life.

Most importantly: for the remainder of that incredible deployment, I was able to lead the Chiefs in combat sorties all across Afghanistan, and then (with Flak Willis) lead our 14-ship of 335th FS Strike Eagles home across the Atlantic for an epic Chief Elephant-Walk at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base.

To this day, if anyone ever asks me what my best mission was in any airplane, I'll tell them it was 20 February 2008, when after going deaf in my left ear one morning, I flew the Mighty F-15E Strike Eagle once again over Afghanistan with three of the finest aviators in the world, doing the mission we were sent there to do.

And to this day, I never, ever, take a single flight for granted.

Hitting the Tanker enroute to Vinoland in Northeast Afghanistan

I cherish the moment every single time I feel my wheels leave the ground in my Super Champ taildragger or in my V-35 Bonanza - in a way I never would appreciate it had I not spent that long cold month, grounded in Germany at the Landstuhl Hospital and at Bagram in my squadron, praying for just one more combat mission in the F-15E.

The Lord has been so very good to me.

.jpg)

.JPG)